The flag of the United States of America fades to black on the gigantic screen. Dancers in golden robes move solemnly across the star-shaped stage. The crowd begins to cheer. Thousands chant her name, eagerly awaiting her arrival.

The sound of galloping horses echoes through the stadium, as if someone were approaching on horseback. The dancers exit. The music of AMERIICAN REQUIEM erupts. Sixty-two thousand people roar, straining for a glimpse of her. They hold their breath.

© Beyoncé

The first song begins, her voice booms through the vast stadium: Nothing really ends, for things to stay the same, they have to change again. Hello, my old friend. You change your name but not the way you play pretend. American Requiem! Them big ideas (yeah), are buried here (yeah). Amen!

© Beyoncé, Beyoncé’s background dancers appear first, all dressed in gold. At each show, however, they wear different colours, ranging from gold, red, blue and white.

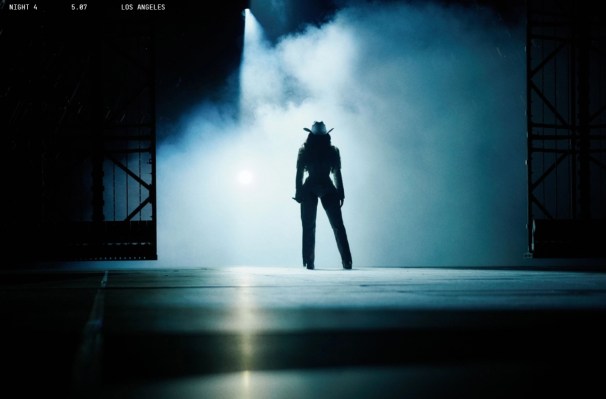

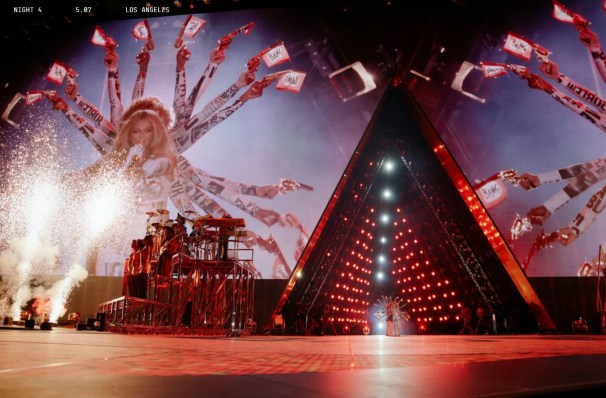

The music chimes, the rhythm intensifies. Once more, the melody rings out—this time, the triangular-shaped gate at the centre of the stage lights up in gold, red, blue, and white. A shadow appears behind the closed gate. It’s the woman they’ve all been waiting for. The crowd erupts in a deafening scream that vibrates through the arena. But the music swells even louder. With the next beat, the gate begins to open slowly. Light bursts forth, revealing the greatest superstar of the 21st century.

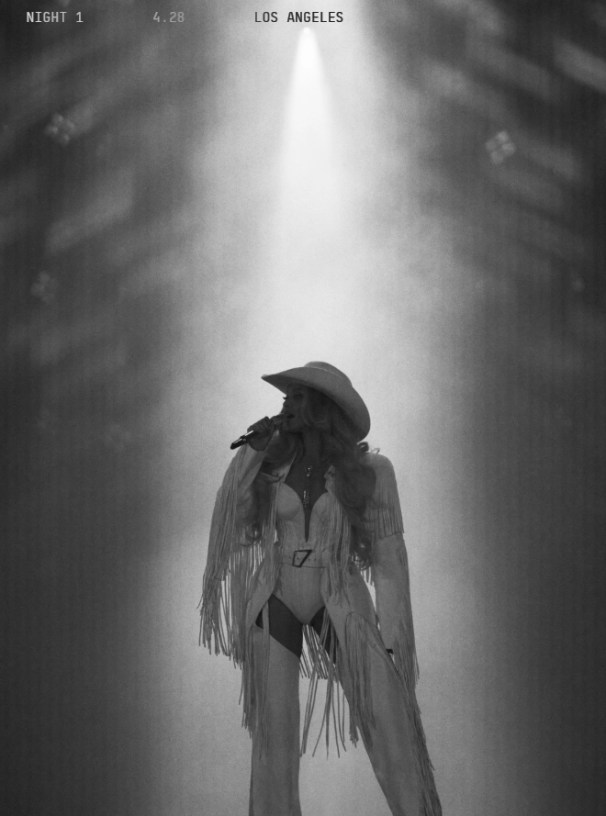

The crowd begins to cheer again—louder than ever before. They still can’t see her face. She looks down, wearing a cowboy hat. Slowly, she raises the microphone to her lips and begins to sing: ‘It’s a lot of talkin’ goin’ on…’

© Beyoncé

The audience erupts in fresh waves of cheers and screams. She stands motionless, taking it all in. Seconds pass. The crowd doesn’t let up.

The next beat drops. She lifts her head. Now they can see her face. The stadium explodes with noise. Beyoncé continues: ‘While I sing my song.’

Again, the crowd roars, and fireworks explode to the left and right. Beyoncé keeps singing as she walks toward the centre of the stage, beginning the first section of her Cowboy Carter and the Rodeo Chitlin’ Circuit World Tour.

© Beyoncé

After the release of her ninth studio album, Cowboy Carter—the second act of her three-part trilogy reclaiming Black music, which began three years ago with the Renaissance—Beyoncé is more successful and captivating than ever.

Two years ago, during her Renaissance World Tour, she rightfully declared that, at this stage of her career, she had nothing left to prove. She possessed the rare freedom of an artist no longer needing to conform—no longer bound by mainstream expectations or driven by commercial success. Instead, she could simply enjoy the creative freedom to do whatever she wanted:

‘You can either take me, or you don’t.’ And this decision made her more successful than ever before.

And in a world growing more uncertain each year, Beyoncé offers not just escapism but also takes the opportunity to raise her voice—speaking out, getting political, challenging social norms, and above all, taking a stand against everything currently happening at the White House.

While Beyoncé has addressed political issues before—making feminism commercially visible with Run the World, or confronting structural racism, gun violence, and police brutality in her Grammy-winning album Lemonade, to name just a few examples—she now goes a step further. With the Cowboy Carter World Tour, she blends her artistry into new forms, creating a concert experience that is both celebration and protest.

© Beyoncé, The stage shaped like a star and a guitar

And she does exactly that from the very start—especially when one considers the lyrics of her opening song, AMERIICAN REQUIEM, which connect past, present, and the high stakes of the future. Even the song’s title alone invites deeper reflection: A requiem is a song of remembrance. Often part of a sacred composition or accompanied by religious texts, it reflects on the past. Traditionally, it is sung at funerals.

And this is where things get interesting. One of the most persistent beliefs held by conservative and far-right politicians is that the past was somehow better.

But that’s not only wrong—it’s a deliberate distortion. The past wasn’t better for everyone. It certainly wasn’t better for women, for the LGBTQ+ community, or for people of colour, to name just a few.

© Beyoncé, Fans in London in Cowboy looks before the show

It’s also true that while some things—especially regarding women’s rights and human rights—have improved over the past few decades, many injustices persist. Conservative and far-right politicians continue to promote convenient falsehoods that serve their own interests. They protect their grip on power and wealth, all while the rights of others—using the U.S. as an example, the rights of women and African Americans—are increasingly under attack. In the worst cases, those rights are being rolled back entirely.

Beyoncé sums up this issue in the very first line of AMERIICAN REQUIEM, her funeral song for the US: ‘Nothin’ really ends, for things to stay the same, they have to change again, hello my old friend, you change your name, but not the ways you play pretend, American Requiem, them big ideas, are buried here, Amen.’

The opening lines make it unmistakably clear: racism, marginalization, and injustice never truly end. The fight is ongoing. And the rights that generations have fought for must be protected—and, if necessary, fought for all over again.

© Beyoncé

The following line might be the most interesting one of the first stanza: ‘Hello my old friend, you change your name, but not the ways you play pretend.’ It echoes the beginning of the song but almost in an exhausted comedic way. Beyoncé cannot be fooled. She recognises the racist, the sexist, the homophobe. It’s an ‘old friend’, she can immediately identify. He might have changed his name, but she knows how he plays. It’s almost like the saying: When the devil smiles at you, you have to smile right back at him.

The final lines, however, strike a more hopeful tone. Beyoncé reminds us that this is a funeral song—for America as it exists today, and for the America of the past. Both are fading, along with the grand ideals that are being buried alongside them. With this new act and genre, she offers an alternative—a new vision for America, where her voice might inspire fresh ideas of hope and healing.

© Beyoncé

As the song progresses, it sheds the weight of the past. The tone becomes lighter, more uplifting—yet remains critical. With a touch of irony, Beyoncé even anticipates the backlash, hinting that both the song and the album will spark controversy. She sings: ‘It’s a lot of chatter in here. But let me make myself clear.’ Not caring about her critics, she continues: ‘Can you hear me? Or do you fear me?’

The first question, of course, is meant as mockery. Beyoncé has over 310 million Instagram followers and is the most decorated artist in Grammy history. When she speaks—or sings—the world listens. She is, after all, American royalty.

© Beyoncé, Beyoncé wears a custom-made body suit featuring an American bald eagle by Burberry

Her second question, however, strikes a more serious note—one that borders on self-reflection. Beyoncé knows exactly what she’s doing: she speaks and sings about issues that conservative and far-right politicians would rather deny, suppress, or leave buried in the past. But with her powerful, commanding voice, she reminds us that America is not—and has never truly been—great for everyone.

This version of America, she suggests, must be laid to rest. Change is not optional—it’s necessary.

© Beyoncé, the last part of the AMERIICAN REQUIEM choreography

Beyoncé seamlessly links the themes of her opening song to the second track in the setlist—a cover of a 20th-century classic: Blackbird by Paul McCartney. Her version, titled BLACKBIIRD, is the first of two covers paying tribute to musical legends. Here, she builds a bridge between the struggles of today’s America—voiced in AMERIICAN REQUIEM—and those of the past.

In 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional. Just three years later, in 1957, nine African American teenagers became the first to enrol at Little Rock Central High School in Arkansas. But the night before their first day, the state’s governor ordered the National Guard to block their entry. The world would come to know these brave students as the Little Rock Nine.

Almost a month later, a federal judge ordered the National Guard to stand down. The students made another attempt to enter their school—this time through a side entrance, as a racist mob was blocking the main doors.

Later, President Dwight D. Eisenhower intervened. He placed the Arkansas National Guard under federal control and sent U.S. Army troops to ensure the Little Rock Nine could safely enter the school and begin attending classes.

Despite ongoing racial harassment from white students, the nine persevered. In 1958, Ernest Green became the first Black student to graduate from Central High School. The story of the Little Rock Nine would go on to become one of the pivotal moments that helped spark the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s.

© Beyoncé

About a decade later, Paul McCartney expressed deep compassion for the Civil Rights Movement—particularly for the struggles of African Americans in the American South. Moved by the story of the Little Rock Nine, he was inspired to write Blackbird:

‘I just thought it’d be really good if I could write something that, if it ever reached any of the people going through those problems, it might kind of give them a little bit of hope,’ Paul McCartney said.

The explanation for the song title comes from England. Here, girls are colloquially called ‘birds’. Then, Paul McCartney thought of a black girl as a black bird and combined this thought with the touching lyrics: ‘Blackbird singing in the dead of night, Take these broken wings and learn to fly, All your life, You were only waiting for this moment to arise.’

The song appeared on The Beatles’ 1968 self-titled double album—commonly known as the White Album—becoming not only a major success, but also a powerful political statement within the record.

© Beyoncé, Beyoncé’s background dancers perform SWEET HONEY BUCKIN‘

Back on stage in 2025, Beyoncé performs the song at every stop of her Cowboy Carter World Tour. She is a Black woman—and now, she gets to fly.

As she sings, images of the Little Rock Nine and prominent female Black singers of the 20th century appear on the giant screens behind her, weaving the sounds and struggles of the past into the present. Once again, just as more than half a century ago, the performance carries a vision of a world with less discrimination and more hope.

These images are followed by a striking visual: Beyoncé in a cream-colored dress, a lace veil draped over her face—a symbol of humility. On either side of her sit two blackbirds. Behind her hangs the American flag, battered and torn. It bears scorch marks, slashes, and dried blood stains—a haunting reminder of the nation’s brutal and deeply problematic history.

At her final concert in London on June 16th, during her mini-residency at Tottenham Hotspur Stadium, Beyoncé took a moment to thank Paul McCartney for speaking out all those years ago. As a tribute, her opening outfit that night was a black-and-white costume featuring two blackbirds across her chest—designed by his daughter, Stella McCartney.

© Beyoncé, Beyoncé wears custom-made Stella McCartney featuring two blackbirds on her chest during her last night in London

But Beyoncé’s political messages don’t end there. In fact, she’s just getting started. After BLACKBIIRD, she transitions directly into the U.S. National Anthem. Yet she doesn’t perform it traditionally—instead, she channels Jimi Hendrix’s iconic Woodstock rendition, which he performed in protest following the assassination of Martin Luther King Junior. Hendrix’s version was a powerful artistic protest against how far America had drifted from its founding ideals: freedom and liberty for all. As Melissa Enchanted, a member of the Beyhive, explains on social media: ‘His version was a protest at how America has moved away from what the country wanted to stand for—freedom and liberty for all.’

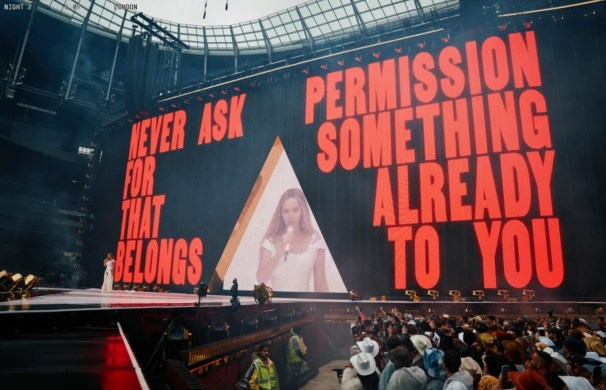

At the end of the National Anthem, a bold message flashes across the stage screens: NEVER ASK PERMISSION FOR SOMETHING THAT ALREADY BELONGS TO YOU.

© Beyoncé

The phrase underscores the enduring fight for civil rights—but it also speaks directly to the roots of country music, a genre born from Black musical traditions and redefined through Cowboy Carter. Beyond that, the message echoes back to Renaissance and affirms the rights and visibility of the entire LGBTQ+ community.

As the words appear, Beyoncé reaches the final line of the anthem—‚O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave’—and seamlessly transitions into her Black pride anthem FREEDOM from the Lemonade album.

The track, powerful and defiant, also served as the campaign song for Kamala Harris’s 2024 presidential bid.

© Beyoncé, Beyoncé on her way to the middle of the stage, performing FREEDOM

FREEDOM is perhaps Beyoncé’s most powerful song—a fierce demand for liberation, not only for herself but for all Black women and women across the United States who have been wronged and suppressed by the patriarchy.

She draws a direct line to America’s history of slavery with the lyric: ‘I break chains all by myself, won’t let my freedom rot in hell.’

This message is amplified even further in the FREEDOM music video. Beyoncé performs the song in front of a group of African American women dining together at a long table—she, their powerful and serene matriarch.

In the background stands a Southern plantation house, framed by the sweeping branches of a live oak tree, iconic to the American South.

Here, Beyoncé draws a powerful contrast between past and present. Once, these very trees were the sites of horrific violence—where enslaved people were lynched by their oppressors. Now, beneath those same branches, Black women gather, dine, and celebrate. The tree that once symbolized terror is reimagined as a sheltering witness to survival, strength, and reclamation.

Beyoncé creates a striking visual and emotional moment. She reminds the viewer and listener of America’s painful past—but through her voice and lyrics, she offers peace and healing. Together with other like-minded women, she imagines a new era rooted in resilience and transformation.

© Beyoncé

FREEDOM is followed by YAYA—a genre-blending track steeped in country and rock ’n’ roll. Here, Beyoncé shifts from direct political confrontation to a more playful and theatrical performance. Yet even in this lighter tone, the message remains. She carries it forward with the line: ‘A whole lot of red in that white & blue, history can’t be erased. Are you tired of working time and a half for half the pay?’

Here, she refers to the bloody ( a whole lot of red) history of America again as well as the hard-working people, Afro Americans especially, who have always suffered from structural racism and always had to work harder than all other white Americans.

Beyoncé then transitions into the final song of the first section: Why Don’t You Love Me, one of her early diva-pop hits, —while still carrying over sonic and visual elements from YAYA.

© Beyoncé, Beyonce performs YAYA while a golden piano lights up on fire

With the first part complete, Beyoncé takes a seat on a golden throne. She lights a cigarette as a robotic arm pours her a glass of Sir Davis Whiskey—a family recipe from one of her ancestors, a former moonshine distiller.

She picks up a remote, presses play, and in a dramatic flourish, both she and the throne descend below the stage. The first set of visuals begins to play. This marks the end of the first section, acting like a prologue for the entire show, setting the themes of the Cowboy Carter and the Rodeo Chitlin’ Circuit World Tour.

© Beyoncé

The first interlude—and its accompanying visuals—are just as political and powerful as Beyoncé’s opening performance. The giant stage screens fade to black. A voice begins to echo through the stadium: it’s Ras Baraka, the mayor of Newark, New Jersey as well as a poet and activist.

He recites the first part of one of his most powerful and widely discussed poems, his voice resonating through the darkened space as the words appear on screen:

Are there any American poets in here?

I wanna hear an American poem

A South Carolina slave shout or

Alabama backwoods church shack call and response

I wanna hear an American poem

An American poem

About share croppers on the side of the road

Of families in cardboard boxes.

Not about kings or majestic lands or how beautiful ugly can be

I wanna hear some American poetry

I wanna hear some American shit

Some American poetry

Something about ghettos of Italians, of Jews, of Germans, of niggas

About abandoned projects and lead poison and poverty and children in jail.

I wanna hear a poem about a picket line and the Joe Hill legend, struggle for an eight hour day

Hey you, hey you

Where are all the American poems about Harlem number runners and barber shop conversations about colored faces on color tvs

I wanna hear an American poem, something American, as American as jazz,

Or a South Bronx burner brandished on abandoned buildings

A scratch tune

A breakbeat

A backspin

A beatbox

A rap song

In Congo Square

Niggas beatin‘ on buckets on Broad Street,

As American as the Zulu Nation and the Latin Kings

I wanna hear an American poem

About a dead girl on Chadwick Avenue with a bullet in her neck

From a cop doin’ his job ordered by Fascism and crack cocaine

You know, something made in the USA

Something American

Baraka’s message needs no deep interpretation—it speaks for itself. His words serve as a direct, unmistakable summary of everything Beyoncé conveyed in her opening section.

In recent months, Baraka has drawn increasing media attention. Beyond his role as mayor, he is a long-standing community activist and one of the most vocal critics of Donald Trump and the Republican Party.

As the poem unfolds, images of Black American life flash across the stage screens—moments of struggle, resilience, and resistance. A beat begins to rise beneath Baraka’s voice, and visuals of Beyoncé slowly emerge on screen, seamlessly connecting his words with the next chapter of her performance.

She appears on screen dressed in a leather cowboy outfit, standing beside a white horse. They’re inside what looks like a surreal living room, with dozens of television screens stacked on top of one another. Together, Beyoncé and the horse watch the news: houses burning, protesters marching, Black voices rising, MAGA followers ranting, and the White House shining under a deceptively calm blue sky.

The visuals shift—Beyoncé rides through a stylised Wild West landscape. Then they shift again: she’s now in the digital frontier of the world wide web.

Here, she draws a sharp parallel between the lawless past of the American West and the chaotic, often hostile world of today’s internet and social media.

She uses this moment to make a broader point: social media and fake news have become breeding grounds for marginalization, manipulation, and division—especially targeting minorities and vulnerable communities.

As these images unfold on screen, Beyoncé’s stance becomes clear, echoed in a statement featured in the Cowboy Carter Tour Book:

‘Right now in the world, the internet is the wild west. There are no rules, nothing to regulate what is truth and what is fiction. An expansive landscape – mostly explored and settled, yet still equally uncharted. Limitless possibilities, very few certainties. This seemingly lawless virtual frontier we know as the internet has no real sheriff, regulations that are too often circumvented, and screens that provide veils of anonymity. The unknown awaits you at every turn, and the truth of your reality may very well be fiction. Ambitious journeys roaming the vast digital terrain are endlessly susceptible to unprovoked breaches of personal peace in the form of harmful rumours, allegations, assumptions, and projections. The hauntingly soft thud of approaching outlaw boots replaced by the incessant keystroke tapping of spreading falsehoods… Secret trickery by the quick witted and sly now appearing as hackers, spammers, and trolls… Artificial intelligence robbing you of your perception and likeness like bandit settlers once did the land… The scorpion sting of algorithmically boosted hate speech. Sure, the dreamers are here building success, creating opportunities, growing community, and innovating through the sense of escape. But your vulnerabilities remain unprotected. This is the world wide web, and the wild wild west. What kind of footprints will you leave in the digital desert sand? Will you cowboy up with the liberatingly dangerous? Or will you just prolong the chaos and folly of destruction?’ (Beyoncé, Cowboy Carter Tour Book, pages 52- 57)

The visuals shift once more—Beyoncé is back in the Wild West. She faces off with an old white cowboy. Calm but firm, she tells him to leave: this is her home, and she doesn’t want any trouble. He refuses. The tension builds. They draw their guns. Shots ring out. But the screen cuts to black before the audience sees how the standoff ends.

The visuals shift once more—we return to Beyoncé in the chaotic living room, surrounded by flickering televisions. She tries to change the channel, but she can’t.

Suddenly, the screens change again. Her tear-streaked face fills the frame. She screams into the camera. Her image multiplies—dozens of versions of herself, all raw and unfiltered. With her bare hands, she wipes the makeup from her face. She cries again. She screams again. Then—darkness. The stage and the screen go black. And finally, a single phrase appears in bold letters across the giant screens: DESPITE THE NOISE WE SING.

The stage is suddenly bathed in red light. The beat drops.

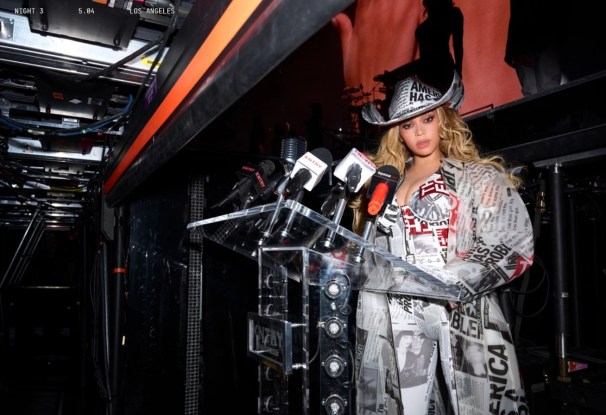

Beyoncé rises from beneath the stage, standing behind a news podium—flawless in a custom-made Diesel bodysuit designed to resemble a newspaper, its pages covered not with headlines but with the titles of her most iconic songs.

Tonight, Beyoncé is the news. She is the anchor, the voice, the message. And she delivers it through the opening track of the second section: AMERICA HAS A PROBLEM.

© Beyoncé, Beyoncé rises to the stage, wearing a Diesel custom-made body suit

The second part of the Cowboy Carter World Tour is just as politically charged as the first—perhaps even more so. And when it comes to choreography and stage power, it’s undeniably on another level. That becomes instantly clear through the intensity and intention of her setlist.

After AMERICA HAS A PROBLEM, the voice of Linda Martell echoes through the stadium. She reminds the audience that Beyoncé doesn’t confine herself to genres—she transcends them. When you are good at it, you can do whatever you want: ‘Genres are a funny little concept, aren’t they? Yes, they are. That Beyoncé Virgo shit. On theory, they have a simple definition that’s easy to understand. But in practice, well some may feel confined.’

Linda Martell was the first African American country artist to achieve commercial success and perform on Nashville’s Grand Ole Opry.

But her career ended almost as quickly as it began—silenced by an industry dominated by white, racist gatekeepers who refused to make space for her in the genre.

During this interlude, Beyoncé and her background dancers take the stage with a visually striking, high-energy choreography. Then the beat drops, and SPAGHETTII begins—a genre-defying track with rap at its core. Toward the end, the song shifts again, this time into Brazilian funk.

© Beyoncé, Beyoncé and her background dancers perform the chorepgraphy for SPAGHETTII

A second dance break follows. Beyoncé and her dancers move to ESSA TÁ QUENTE by DJ Mimo Prod—delivering one of the most electrifying moments of the show.

Moments later, the music fades—then, a familiar beat drops.

The crowd erupts. They know exactly what’s coming. Beyoncé and her dancers fall into formation. One dancer steps forward and hands her a black cowboy hat. With a smooth, deliberate motion, she places it on her head.

She begins performing FORMATION, the lead single from her acclaimed Lemonade album.

The song is a bold anthem about identity, racism, Southern roots, gun violence, and the political unrest that continues to shape the United States.

© Beyoncé, Dancers getting in formation

But this time, it opens with a countryfied twist—once again blurring, mixing, and reclaiming genres. The beat picks up pace. Then suddenly: Silence. Beyoncé gazes out at the crowd. The moment hangs in the air—tense, charged, intentional. She holds the anticipation of more than sixty thousand people in one space. A heartbeat later, with unwavering clarity, she delivers the first lyrics: ‘My daddy Alabama, momma Louisiana. You mix that negro with that Creole make a Texas bama. I like my negro heir with baby hair and afros. I like my negro nose with Jackson five nostrils. Earned all this money but they never take the country out me!’

Here, she pauses again, waiting for the crowd’s reaction. They scream. She repeats the last line: “I said, they never take the country out me!”—reminding everyone that she has always been country. The crowd erupts in cheers and jubilation.

The beat hits, and Beyoncé performs the rest of the song with plenty of swag and hot sauce in her bag.

© Beyoncé

After this powerful moment, she transitions from FORMATION’s urban contemporary style into MY HOUSE, the bonus track from the Renaissance album, blending house and rap. Here, she brings in another reference from a 20th century musical icon. When she reaches the final part of MY HOUSE, she stops singing and adds a dance break. Once again, giant letters appear on the screens: THE REVOLUTION WILL NOT BE TELEVISED.

This phrase, of course, refers to Gil Scott-Heron’s song from the 1970’s, a song Beyoncé has grown up with. The song was also meant as a wakeup call for Afro Americans and how important it is to actively participate in social and political movements. At the end of the little dance break, Beyoncé continues singing: ‚Lend your soul to intuitions, Renaissance the Revolution, Pick me up even if I fall, let love heal us all.‘ A second phrase appears: THE REVOLUTION WILL BE LIVE.

© Beyoncé, Beyoncé and her dancers at the front of the stage

Then, Beyoncé finishes the song with swag and power and moves into Diva, one of her all-time hits from her Pop Queen era.

By the second section, it becomes clear what Cowboy Carter and the three acts of her album are all about. It’s not only about reclaiming genres that are inherently African American and Black—it’s also about breaking them open.

Musicians can blend them, mix them, reshape them. No genre belongs to one ethnicity or one group of people. When music is shared freely, and driven by passion, it can belong to everyone.

© Beyoncé, Beyoncé performs FLAMENCO in Ferragamo

The third and fourth sections of the concert begin on a quieter note, diving into the beauty of country music. Beyoncé opens the third section with ALLIIGATOR TEARS, followed by JUST FOR FUN and PROTECTOR.

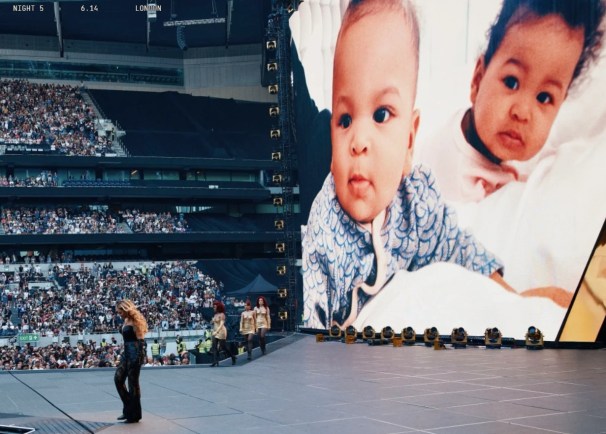

During this part, images of her children appear on the screen, blending with serene visuals of life in the American South.

© Beyoncé, Beyoncé at the centre of the stage while visuals of her children appear on the screens

During PROTECTOR, Beyoncé brings out her daughter Rumi, who waves to the crowd. Her firstborn, Blue Ivy, performs a choreography alongside the other background dancers.

© Beyoncé, Rumi on stage for PROTECTOR

Since becoming a mother, Beyoncé has been highly protective, carefully choosing when and where her children—or even images of them—are shown to the public. With the Cowboy Carter World Tour, Blue Ivy fully steps into her mother’s work ethic, performing more than half of the choreographies with the other dancers. Just as Blue Ivy had her stage debut during Renaissance, Rumi now has hers on the Cowboy Carter World Tour.

Beyoncé is able to guide and show her children what it means to be a public figure—while doing so in front of a trusted audience: the Beyhive, her loyal fanbase. In this way, she can prepare them for the future and teach them how to navigate the attention that comes with being the child of a global superstar.

© Beyoncé, Beyoncé performs TYRANT on a golden mechanical bull wearing Moschino

The fourth section begins with DESERT EAGLE, where the atmosphere and musical elements of country deepen and gain momentum.

DESERT EAGLE is followed by RIIVERDANCE and II HANDS II HEAVEN. After the powerful and politically charged first two sections, Beyoncé’s third and fourth parts are a celebration—of country music, of Black culture, and of its rich and complex history:

‘The emotional vulnerability and spirituality of ALLIIGATOR TEARS and II HANDS II HEAVEN are reflections of the pageant life, rodeo trail rides, and cowboy hats, while SWEET HONEY BUCKIIN underscores the American pride demonstrated in Cowboy Carter through Beyoncé’s own personal, lived experiences. In BODYGUARD and PROTECTOR, the sentiments of a devoted feminine defender proclaim the radical audaciousness of Henrietta Williams Foster, Cathay Williams, Mary Fields, Aunt Clara Brown, Bridget Mason, Johanna July, Sacagawea, Susie Summer Revels Clayton, and countless other women, artists, business owners, and outlaws. YAYA channels the savvy persistence of theatre, nightclub, juke joint, and saloon owners throughout the Chitlin’ Circuit and the creative prowess of artists like Sister Rosetta Tharpe and Roy Hamilton. In the past, we weren’t country enough, we were too country and improper. So, when you hear the banjos, bluegrass elements, boot spurs and whiskey references, and folky storytelling, may it elucidate the truth that we’ve been here, been country.’ (Beyoncé, Cowboy Carter Tour Book, page 5)

© Beyoncé, Beyoncé performs during the third section of her concert, wearing Alexander McQueen

Each section impresses sonically in its own right—but it’s just as important to note that the Cowboy Carter World Tour, like the Renaissance World Tour before it, is also a full-scale fashion show. At every concert, Beyoncé and her background dancers appear in entirely new looks for at least two to four sections. This means that with each concert, fans see Beyoncé in a minimum of three new outfits.

© Beyoncé, Beyoncé performs ALLIIGATOR TEARS in Dolce & Gabbana

Sparkling Loewe bodysuits, Dolce & Gabbana gowns, Burberry faux fur coats and leather boots, Versace mini dresses and stilettos, Balmain ensembles, or Vivienne Westwood haute couture—you name it, Beyoncé wears it.

And of course, every look carries deeper symbolic meaning, referencing cowboy culture, ballroom aesthetics, or Black history in one way or another:

‘Beyoncé channels the beauty, humor, and critical commentary in the compelling cultural magic of country society’s caricatures. A marvel of classic portraiture that ties absurdity with authenticity, staged and posed to model country glam in exaggerated and surrealistic photography. Observe Cowboy Carter’s transformational embrace of duality, and the power of femininity. This ain’t a one-trick pony. It’s a badass Southern woman and she’s lassoing back everything that’s hers.’ (Beyoncé, Cowboy Carter Tour Book, page 73)

© Beyoncé

Halfway through the show, Beyoncé reminds her audience that she is the biggest, the largest force in the game. In the next interlude, a towering, larger-than-life Beyoncé (400-foot giant to be exact) rises from a swamp, shaking the earth beneath her as she strides toward a Southern town. She pours Sir Davis Whiskey into a water tank and keeps walking.

© Beyoncé, The visuals on the screen. Beyoncé lights a cigar with the flames of the Statue of Liberty

She reaches New York City, lighting a cigar with the flames of the Statue of Liberty, then crosses the Atlantic and arrives in Paris. A banjo begins to play as she returns to the U.S., walking through the Texan desert.

Here, a group of white old cowboys gaze at her, mesmerised by her beauty and grandeur. She places a yellow glowing sign in the sand proclaiming: TEXAS HOLD ‘EM.

© Beyoncé, Beyoncé performs TEXAS HOLD ‚EM with an army of background dancers

The first beats of Cowboy Carter’s lead singledrop. The crowd erupts. A truck rolls down a desert road. Neon lights flash. Cowboy boots sparkle. Caricatures of Beyoncé glow in yellow and red.

The giant stage opens. A silver-blue truck drives onto the scene, carrying Beyoncé and an army of background dancers seated on a built-in platform.

The crowd roars once again. Beyoncé smiles at her audience and asks: ‘Can I take y’all to Texas?’

The rodeo begins!

To be continued…

Sources:

americansongwriter.com

Beyoncé.com

biography.com

Cowboy Carter Tour Book

Genius.com (lyrics)

GQ Interview with Paul McCartney

Levelup Online Magazine

Rollingstones.com